Do average prices help customers forecast and evaluate their options properly? No. Here’s why.

Consider the case of the statistician who drowns while fording a river that he calculates is, on average, three feet deep. If he were alive to tell the tale, he would expound on the “flaw of averages,” which states, simply, that plans based on assumptions about average conditions usually go wrong. This basic but almost always unseen flaw shows up everywhere in business, distorting accounts, undermining forecasts, and dooming apparently well-considered projects to disappointing results.

“The Flaw of Averages” Harvard Business Review, by Sam Savage, November 2002.

An energy manager at a large facility with many many utility accounts asked us this question:

“Quick Question: Please provide us with Kilowatt hour price averages in NYC in the last 12 months and forecasts that look ahead 12 months. Can you point us to a website or something?”

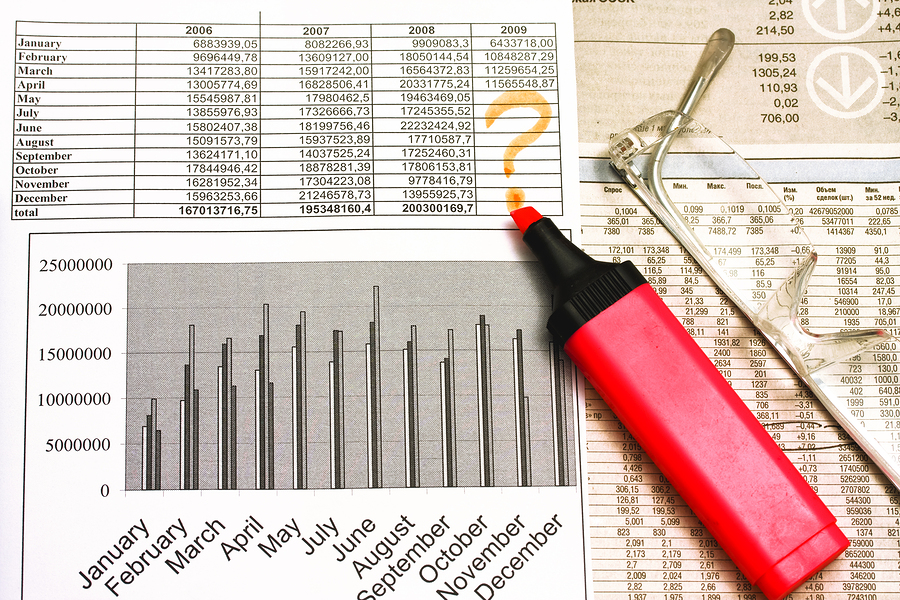

This question reminded us of the temptation that we all have to rely on averages. Many people do that because usually there isn’t any other information available. The result is that often businesses under-estimate risk or make erroneous forecasts or simply make their own work more challenging, and less predictable, by relying on some ill-defined average number.

Customers face this conundrum all the time– how do I forecast?

This flaw is even more true in the case of reporting on and forecasting energy costs. Energy costs are comprised of various components, which are driven by different building or facility characteristics. (You can see a break down and explanation of costs here.) As a result, two buildings may show exactly the same usage but month, day or even the hour of their peak usage may be dramatically different (one building may peak in the Winter, the other in the Summer). All of this data contributes to dramatically different cost histories and forecasts.

Here’s how we answered the energy manager’s question:

Each individual account will have different historic and forecasted numbers. If you’re looking for this information for budget purposes, an average will be wrong without an account-specific forecast– the rate class will get you closer, but not close enough. By way of example, we have a client that has a high load factor– their historical prices are 20% lower than other accounts in the same rate class. Each account’s usage and demand profile has a significant impact on costs– both delivery and supply. We can’t give an historical number without more information. And neither historic nor forecasted costs are meaningful at an aggregate, generalized level.Finally, there is no public website that has a forecast of costs at the retail level. That’s one of the reasons we built The Megawatt Hour. You may be able to access wholesale power prices– but getting that information alone is like asking about the cost of pork bellies at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange– it will not get you to the cost of a BLT sandwich at your corner deli. You will not get a number that is meaningful for forecasting purposes, in part for the reasons I just described.