Conversion of fuel oil to natural gas for heating buildings in New York City has been under way for several years now.

According to the New York City’s Mayor’s Office of Sustainability,

Just 1 percent of all buildings in the city produce 86 percent of the total soot pollution from buildings-more than all the cars and trucks in New York City combined. They do this by burning the dirtiest grades of heating fuel available, known as residual oil, or #6 and #4 heating oil.

Thanks to a 2011 City Regulation put in place during the Bloomberg administration, fuel oil types #4 and #6 are being phased out. Buildings that burn fuel oil will either need to convert their boilers to dual fuel, convert to natural gas or purchase ultra-low sulfur Number 2 oil (see below, from the same site).

In April of 2011, upon the release of the PlaNYC update, Mayor Bloomberg finalized a New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) rule (in PDF) that will phase out the use of two highly polluting forms of heating oil-Number 6 oil (No. 6) and Number 4 oil (No. 4). The regulations were designed to balance near-term pollution reduction with minimizing costs for buildings. Details are below:

Effective immediately, no new boiler or burner installations will be permitted to use No. 6 or No. 4 oil, and instead must use one of the cleanest fuels, such as ultra-low sulfur Number 2 oil (No. 2), biodiesel, natural gas, or steam.

Beginning July 1, 2012, existing buildings that use No. 6 oil must convert to a cleaner fuel (low-sulfur No. 4 oil or cleaner) before their three-year certificate of operation expires. This will result in a full phaseout of No. 6 oil by mid-2015.

By 2030 or upon boiler or burner replacement, whichever is sooner, all buildings must convert to one of the cleanest fuels.

Compliance waivers will be considered through the New York City Department of Environmental Protection.

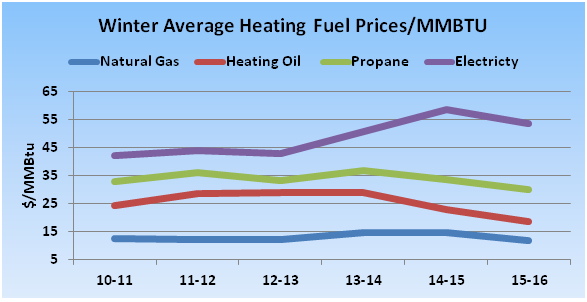

Fuel oil to natural gas conversions are happening all over New York City–and throughout the Northeast. The motivations are not only environmental, they’re economic as well. The following graph from the Massachusetts Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs presents the case convincingly:

There are good reasons to evaluate all options before making a choice. Most residential buildings are expressing a preference for natural gas, since it is both lower cost and burns more cleanly than fuel oil.

What should a building consider when contemplating a conversion?

- Who pays for the conversion, your business or building, Con Edison or a third party?

- If anyone other than you is paying for the conversion, then it is critical to get all the details about the costs and financing, and to make sure that all the facts are transparent.

- What is the implied cost of capital for the project?

- Is it higher than what it would cost you to get a loan from a bank?

- What is the return on investment on the project?

- What are the cost forecasts and assumptions that the financing entity is using to develop the project financing? Are the numbers and assumption realistic?

2. What does the project financing entity expect in return for financing your project? Do they expect a long term contract with your building? What do you give up by making a longer term commitment to one entity?

- We have had some experience with clients who have signed long term agreements with a supplier in exchange for financing fuel oil conversion. In some cases, the supplier has committed the client to a fixed contract as long as 4 years long 2 years prior to the start of the contract.

What to do, what to avoid?

Insist on transparency in every step of the process

Build in an extra 6 months of delays, permitting issues, etc.

Get forward market transparency on any long term agreement that you are considering signing to finance a project.

Don’t agree to a price 2 years before the contract starts, especially if you have no visibility into forward prices. Why? Because signing a contract now for a 4 year term when the contract won’t start for another 2 years will most certainly bring significant additional premiums– the greater the uncertainty, the higher the supplier premiums.

Bottom line for buyers: Our message is simple and consistent– insist on transparency, simplicity and clarity.