Guest post by Michael Fanelli

More and more, it seems consumers are concerned about the availability and accessibility of power sources, especially for the various devices that have come to power our lives. Where is the nearest outlet? Should I charge my phone before leaving the house? Will I be able to find power and WiFi on the plane to Phoenix? While I’m away, what if there is a storm and I lose power? What will happen to the food in the freezer if there is a blackout? This issue of the reliability of power supplies is underscored as we observe the horrific flooding in Texas and the significant challenge to the power grid experienced there and the menace of another Hurricane rolling through the Caribbean, the Gulf and headed to Florida. A recent article in Greentech Media describes how the grid has been tested during this extreme weather event (see “Hurricane Harvey Is Putting Texas Grid Resiliency to the Test”).

Recently, however, we have seen some events that suggest that, in fact, parts of the country are burdened with a power glut, not a shortfall. California is experiencing significant economic repercussions due to excess power. In an article titled “Californians are paying billions for power they don’t need” published earlier this year, Ivan Penn and Ryan Menezes of the Los Angeles Times chronicled the misuse of taxpayer funds and the unintended consequences of a once-helpful policy.

Around the year 2000, the California economy was rapidly expanding, resulting in corresponding increases in energy demands. The state’s existing infrastructure couldn’t support such rapid growth, and residents experienced a series of blackouts. In order to calm the intense criticism that followed, California state officials partnered with utilities to rapidly increase the state’s power supply. They created financial incentives for utility companies to build new power plants rather than increase efficiency at existing ones. The result was a construction boom that gave rise eventually to 500 additional power plants in the state, beginning with the highly publicized Sutter Energy Center, which was expected to have a life span of 30 to 40 years.

However, during this constant stream of construction, energy usage in California dropped due to the pressures of the Great Recession combined with an increase in the popularity of solar power. At the same time, the power supply of California skyrocketed 43%, resulting in much unused capacity. In fact, by 2015, 831 plants or 71% of all the plants in California were being operated at less than one-third capacity. This caused many traditional power plants to shut down. The Sutter Energy Center closed only halfway through its expected 30-to-40-year lifespan.

Well, I mentioned severe economic repercussions before, so what are they? Penn and Menezes explain that while electricity prices continue to decline throughout the country, California’s rates jumped 12% since the state’s electricity usage began to drop in 2008. This is counter-intuitive, as it is logical to expect rates to decrease as usage decreases. So what’s going on here? The short answer is: overcapacity isn’t cheap. According to the authors, taxpayers pay $6.8 billion each year to keep 71% of the state’s power plants running at less than one-third capacity. To make matters worse, regulations continue to guarantee a profit for utility companies if they keep building more plants, so that is exactly what they are doing: building more plants that further exacerbate California’s power glut problem.

What about other parts of the country, like New York?

What if you don’t live in California? Is our nationwide electric grid exposed to this type of mismanagement by public officials and utility companies? Is New York doing anything to address this kind of policy-gone-wrong? The answers to the latter two questions are “not in any tangible way” and “yes.” Consumers in New York can breathe a sigh of relief as there has been no sign of a power glut in New York. In fact, much of the opposition to the closing of Indian Point was concern over not having enough energy to sustainably replace the nuclear power plant that supplies 25% of NYC’s and Westchester’s power.

Even so, there is an effort in New York to adjust the structure of our electricity grid. Since our electricity system is heavily focused on managing peaks in demand, there are bound to be surpluses during off-peak hours. In addition, our electricity system is designed to produce more energy than is required at normal peak times to account for partial outages. This system of creating more energy than we use during peak hours has been described as gold-plated; New York has been working to adjust this gold-plated system by trying to flatten those peaks and thus decrease our required energy capacity.

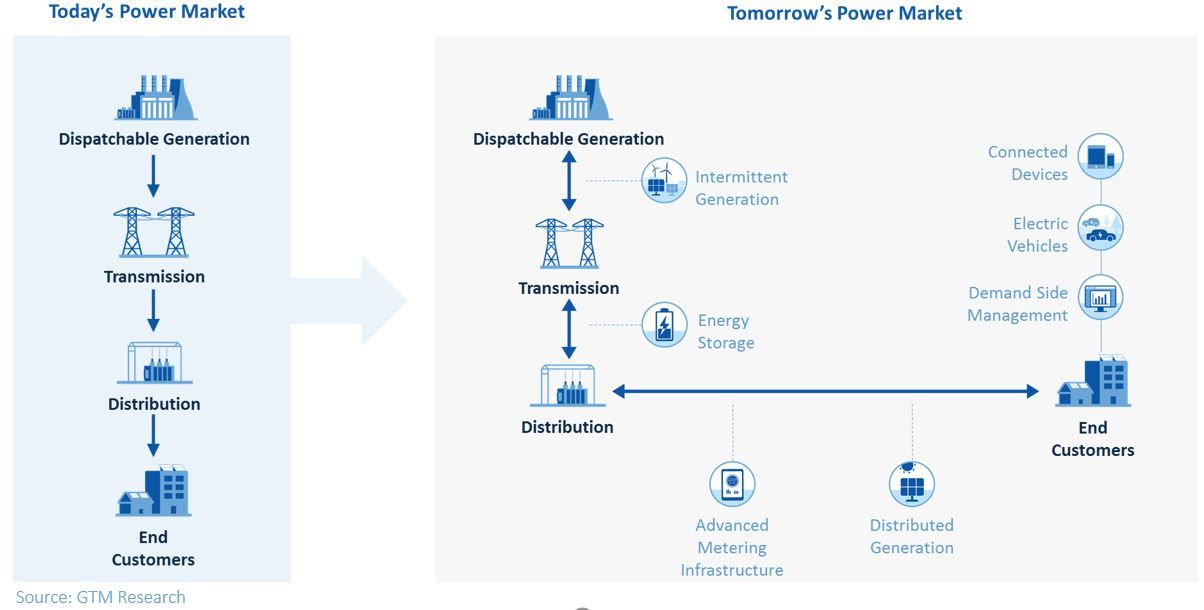

In a 2014 article on NPR titled “New York Says It’s Time To Flip The Switch On Its Power Grid”, Yuki Noguchi reports that New York is trying to move from the current grid-like model to more of a network model. This effort, known in the State of New York as “Reforming the Energy Vision” or REV, is an effort undertaken by the NY Public Service Commission and Governor Andrew Cuomo and has been underway since 2014. The goal is to address both resiliency concerns (of the sort currently being experienced in Texas) as well as concerns about how to properly size and supply consumers with power and energy. It acknowledges that the power industry is in transition thanks in large part to technology changes.

This network model would utilize energy storage and renewable energy sources to create a broader marketplace for energy, allowing for decentralized distribution. Noguchi explains in further detail that “Some utilities are already doing some limited versions of the model, like reselling power. But under New York’s plan, […] customers would be able to sell their power for more at peak times, for example. Electric cars might get charged every time the sun shines on a solar panel or when the wind blows through a turbine. New companies might sell services to customers that optimize electricity use to all key appliances.” This is more than just designed to closely manage costs. This new network system is also expected to increase resiliency.

Perhaps the most encouraging sign for ratepayers’ pockets is New York’s cooperation with utility companies. Rather than simply creating incentives for utilities to build new power plants, Noguchi explains that New York intends to create a “model that gives the utilities incentives to create greater system efficiency so that, if they actually reduce demand or promote energy efficiency, they can make money.”

Examining the challenges to California’s electricity supply system provides insight into the relationships between consumers, policymakers, and utility companies. Meanwhile, New York State’s Reforming the Energy Vision, and the challenges to its implementation, reveal that there is still much work to be done to improve our electricity grid. New York’s new plan to increase reliability while decreasing costs could –if it works as planned — point the way to correctly creating incentives for utilities while maximizing benefits for all parties involved. With the right incentives for all stakeholders, perhaps we can be confident that we have the right power system for our future requirements. We can clearly understand what is driving our costs and usage, and feel confident that our devices will remain powered up, our steak won’t spoil in an outage, and that the system is resilient and sustainable, both economically and environmentally.

Michael Fanelli is a student at University of Michigan with an interest in engineering and business.