Guest post by Tom Leach, Scientific Air

Your lobby should be warm even if it is 10 degrees outside.

Your tenants and guests expect comfort under the most extreme circumstances. You should too.

You know how good your health is after you run through the airport carrying your briefcase and your overnight bag. Your building is the same way; when it is strained, the health of the building becomes clear. The cold weather we’ve experienced so far this year can tell you a lot about your building operation. It can also provide you with insights about how best to manage energy costs.

The recent bout of extremely cold weather put a stress test on heating systems. The ultimate passing grade for a building is a warm lobby when it is 10 degrees outside and the wind is blowing.

Every building’s HVAC system is designed to provide comfort and comply with local building codes. From the initial design, through construction and operation of a building sometimes things are missed, not connected, turned off or simply broken or worn out.

Heating systems have to “work” to maintain a comfortable temperature difference between the inside of the building and the outside. If we want to hold 70 degrees inside, the heating, ventilating, and air conditioning system (HVAC) has to work twice as hard when it is 50 degrees outside versus when it is 60 degrees. (70-50 = 20 degree difference, 70-60 = 10 degree difference, 20/10 = 2X).

How does cold weather impact my building?

The average temperature in NYC for January 2018 was 33 degrees F. The coldest day, January 7, 2018, had a low of 5 degrees. On that cold day, the HVAC had to work 75% harder than the average to hold a 70-degree lobby (70-33 = 37, 70-5=65, 65/37 = 1.75 or 75% more). Many buildings could not keep up. The result was cold buildings and unhappy tenants and guests.

This recent cold stress test exposes problems that have often existed for years but have never been exposed because the HVAC didn’t need to run at a full 100% capacity. The types of issues that we have recently discovered in customer’s buildings include:

- The wrong size heating coil installed in the lobby’s air handling unit.

- Valves were left closed after service work was done.

- Dirty filters blocked air flow.

- There was no return air flow path and the restaurant was pulling in 100% fresh air.

- The radiant heat valve hadn’t worked in years.

What does this mean to me as a building owner or manager?

Temperature extremes expose building operation weakness. They also put building owners in a reactive mode. You are forced to overcome building issues while occupants are freezing and can’t work or enjoy their stay in NYC. Your building is struggling in the same way some people struggle with health issues when they are out of shape.

These building failures mean that you are spending more than you should to operate your building. (For recent articles on how cold weather has impacted energy markets, take a look here.)

Most buildings compensate for problems by increasing boiler water set-points and increasing the speed of the pumps. Both are fine for a short-term solution but mask an underlying problem(s). Often building operators keep applying these fixes until they are no longer effective at correcting the problem. These adjustments also increase the energy cost of the building beyond what is required if the system was operating properly.

A specific example from a recent visit

The following story illustrates the point where a building was designed to have the system work harder than it should.

I visited a hotel in NYC (~ 300 rooms) that was considering control upgrades. In the first walk around I found the following issues in the heating system:

- The heating pumps run 24 hours per day, all year round even during the summer. Just shutting down the pumps when the outside air temperature exceeds 70 degrees will yield $2,700 in electric savings from not running the pump. This will also remove a load off the AC system in the summer as the hot water isn’t heating up the building.

- The pumps for the chiller plant always run at 100% speed when operating. During the cooler months when the cooling load is lower it pays to slow down the pump’s speed to match the demand for cooling. Electric savings from the chilled water pumps are expected to be $47,500/year. A 3-year payback is expected from the full upgrade).

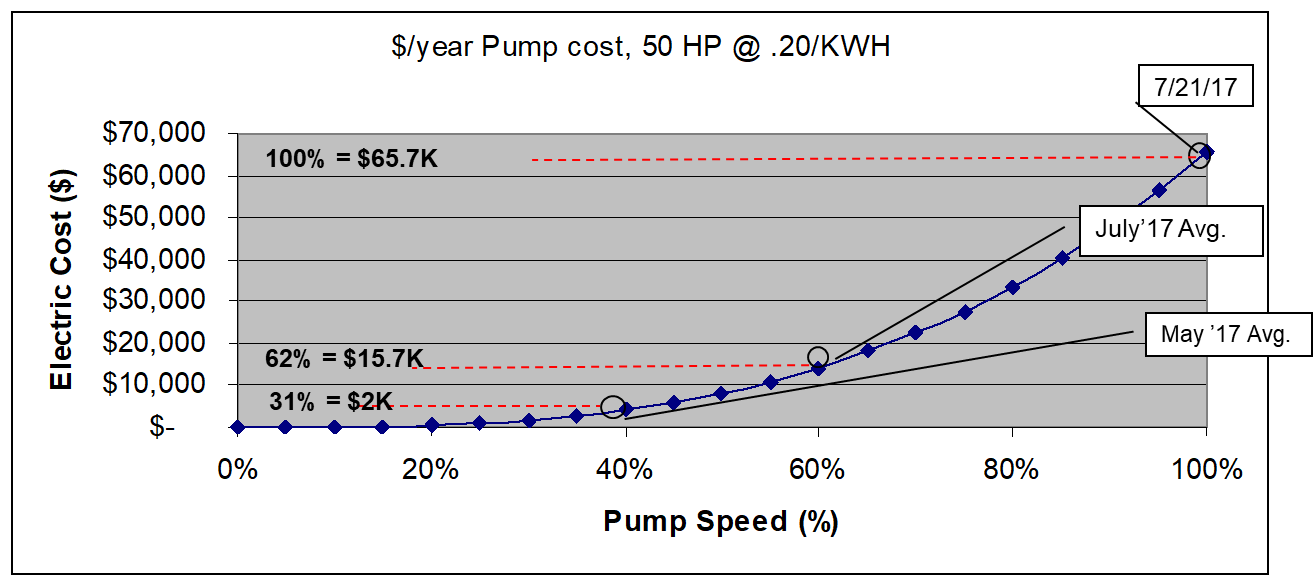

Here is why pump speeds are so critical to operating a building efficiently. Pumps move water based on the speed they are run. A pump at 50% speed moves ½ as much water as when it runs at 100% speed. Pumps consume power at the cube of the speed! So a pump at 50% speed only consumes 12.5% of the power (.5 * .5 * .5 = .125).

Energy cost management and building design

The graph displayed below shows how the building’s design can result in inefficiencies. This graph shows the cost of running the pumps for a hotels AC plant at various speeds. This pump was designed to handle the 95-degree day that occurred on 7/21/17. Designing for the peak day and not adjusting pump speeds for lower loads means that, the rest of the year the pump is moving too much water and the building is paying for it. During the month of July, the average operating point of the pumps can drop to 62% which saves 74% of the pumps energy (1-(.62*.62*.62)). (On my visit in January 2017 the pumps were running due to the load from people in the lobby, I’d estimate the load was less than 10% of system capacity, but the pumps were at full speed.)

What is the impact for your customers, tenants, and guests?

A building tune-up has a direct impact on customer experience as well. Hotel operators tell me that they live and die by the customer comments on sites such as Trip-Advisor. Bad experiences with the room comfort are no longer confined to the front desk; the whole world knows when your customers are cold.

I stayed in a hotel in Boston in January 2018; I had to change rooms because the heating unit couldn’t get the temperature above 63 degrees. In this case, the revenue that room could have generated was lost. The room was uninhabitable below 15 degrees outside. I’m less impressed with this large chains operation. Yes, they have a zippy internet-enabled TV but it was on no use as I couldn’t sleep in that room.

Is there a silver lining to this story?

The interesting part of the story is this; a building operator can use the cold weather stress test to pin-point where the system is failing. Then the building operator can focus on what needs to be done both for customer comfort and energy savings.

Bottom line for building operators and financial decision makers: Figure out your system weaknesses are before your building is stressed. Be proactive and solve problems ahead of time before it affects your revenue.

Nothing is better than full occupancy, satisfied tenants, and happy customers.

Tom Leach is a principal with Scientific Building Automation, a controls company that does both new and retrofit controls for HVAC systems in the NYC metro area. Tom has written numerous articles and his latest publication is in the ASHRAE Journal, “How to Implement a BACnet system” about HVAC controls in a new 150 room NYC hotel.

You can reach him at tleach@scientific-air.com

www.scientificba.com